Concrete Problem: Exploring the context

In the discovery phase we aim to understand the problem space ahead. This is necessary to prevent professional deformation (McRaney, 2012) from biasing our design. We familiarise ourselves with the context our design will have to function in, and try to understand our target audience.

We do this by conducting research. Erika Hall defines (2013) four different types of research, the first being generative research. Here we "don't know what we don't know", and we try to find a problem to latch onto. We throw out a net and see what gets caught.

Once you start getting answers, you’ll keep asking more questions.

Generative research requires a very open mind, free of assumptions. It's easy to not explore a certain problem or audience because we judge it preemptively.

Design research requires us to approach familiar people and things as though they are unknown to us to see them clearly.

Once you have found a clear problem to explore further, you typically move into descriptive research to understand the problem on a deep level. This is the type of research that where the aim is to explain why things are a certain way, what's important to certain people, or how certain things (don't) work. Here, you start asking more specific questions and get obsessed about really subtle motivations and behaviours.

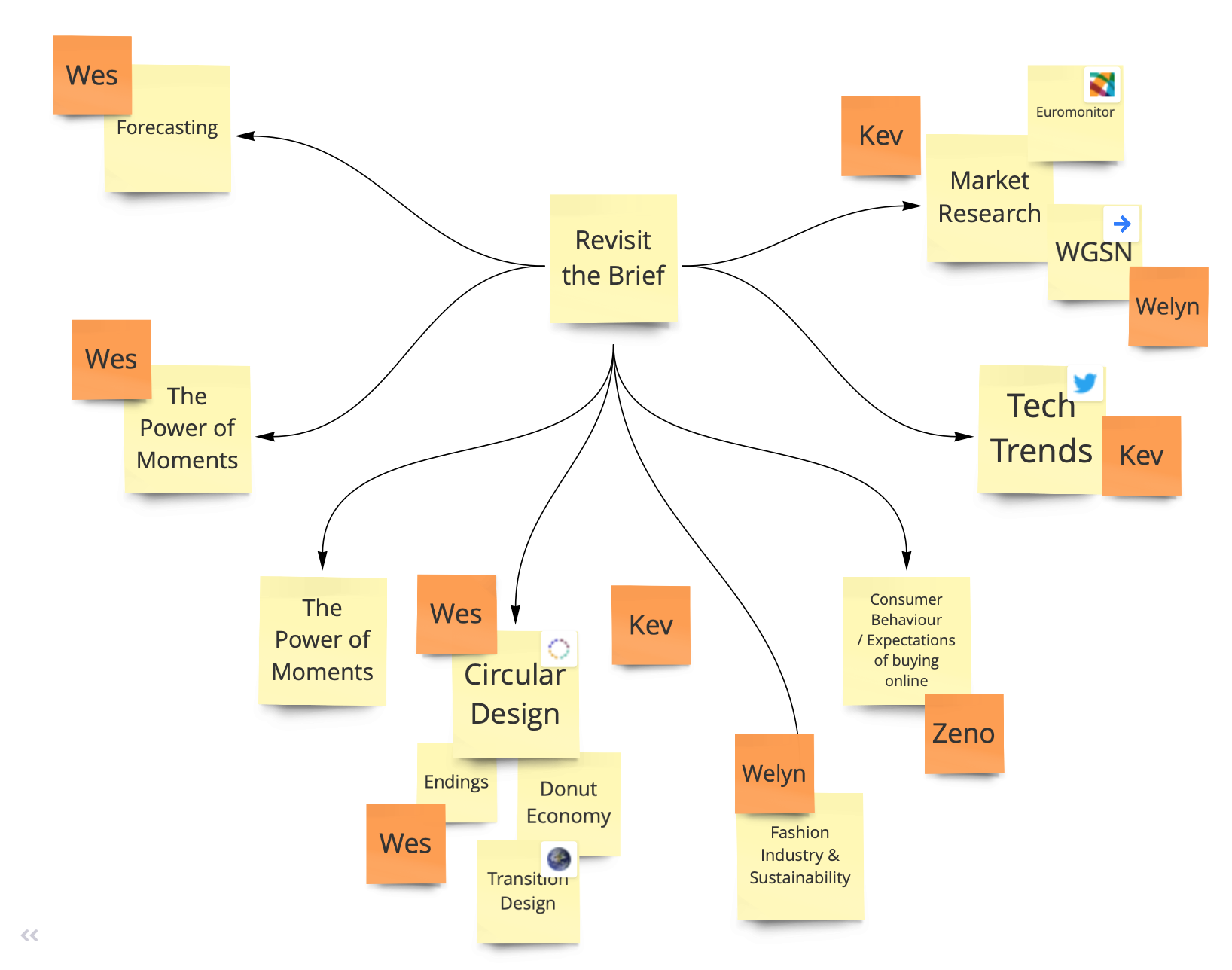

What we did

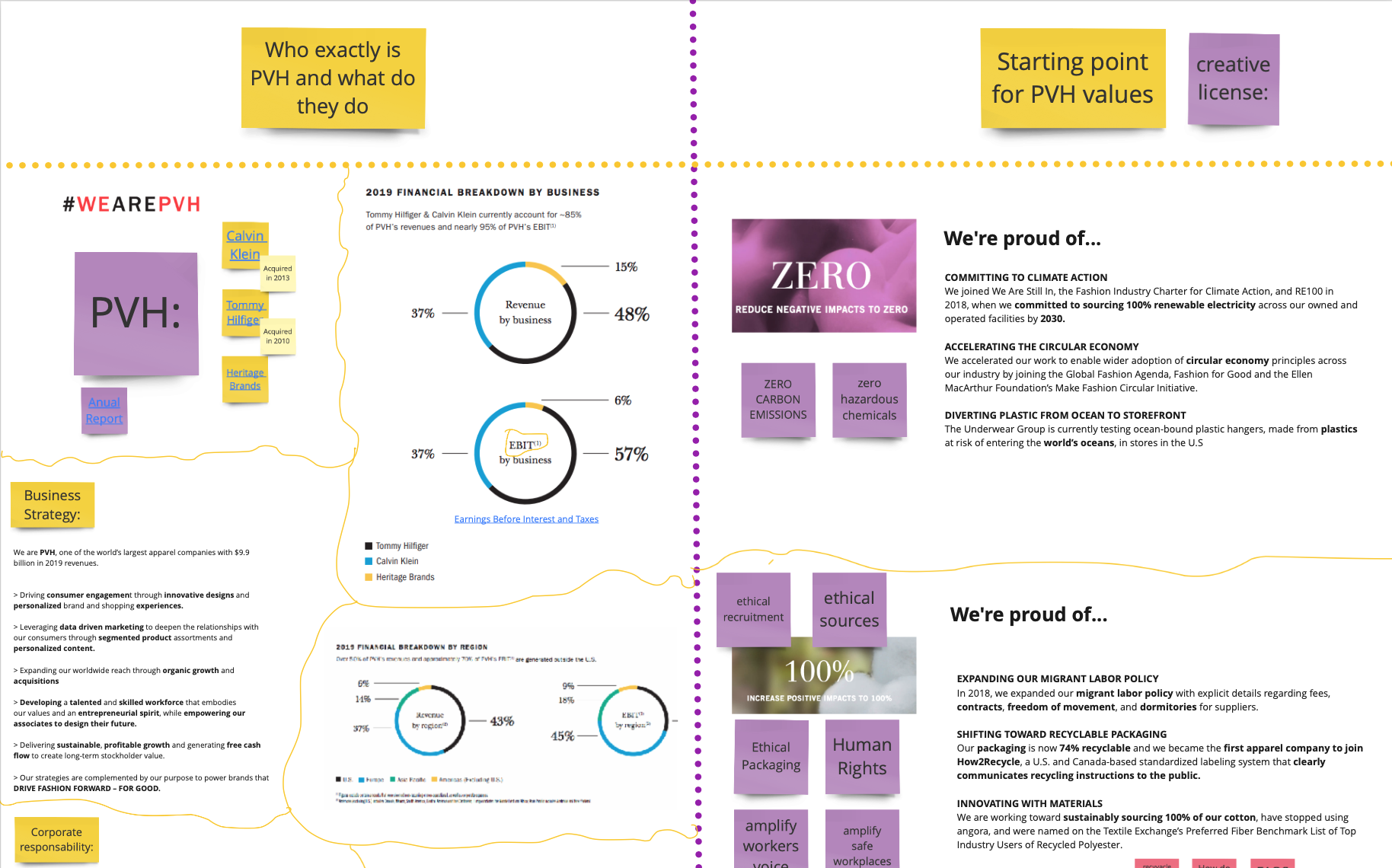

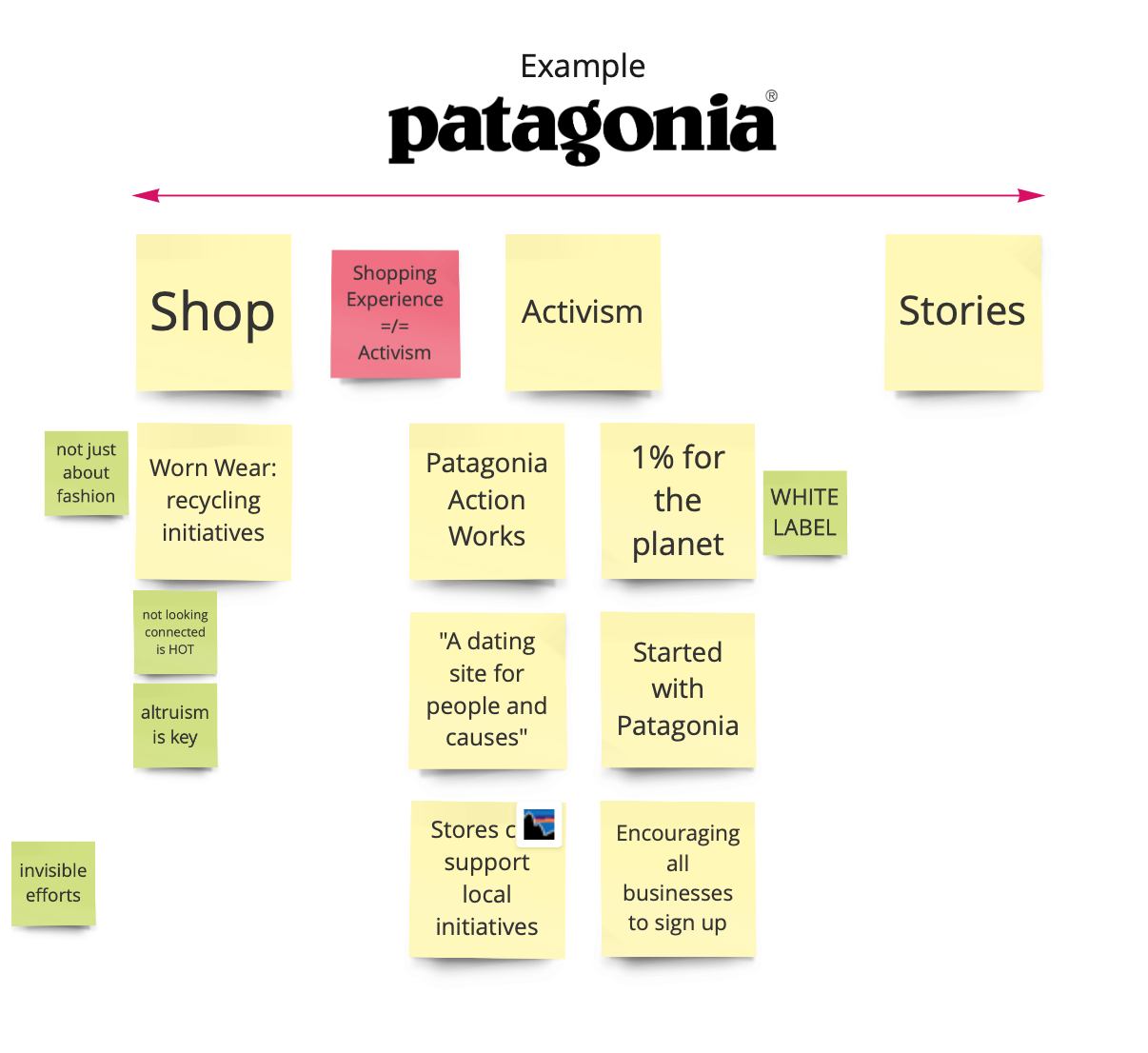

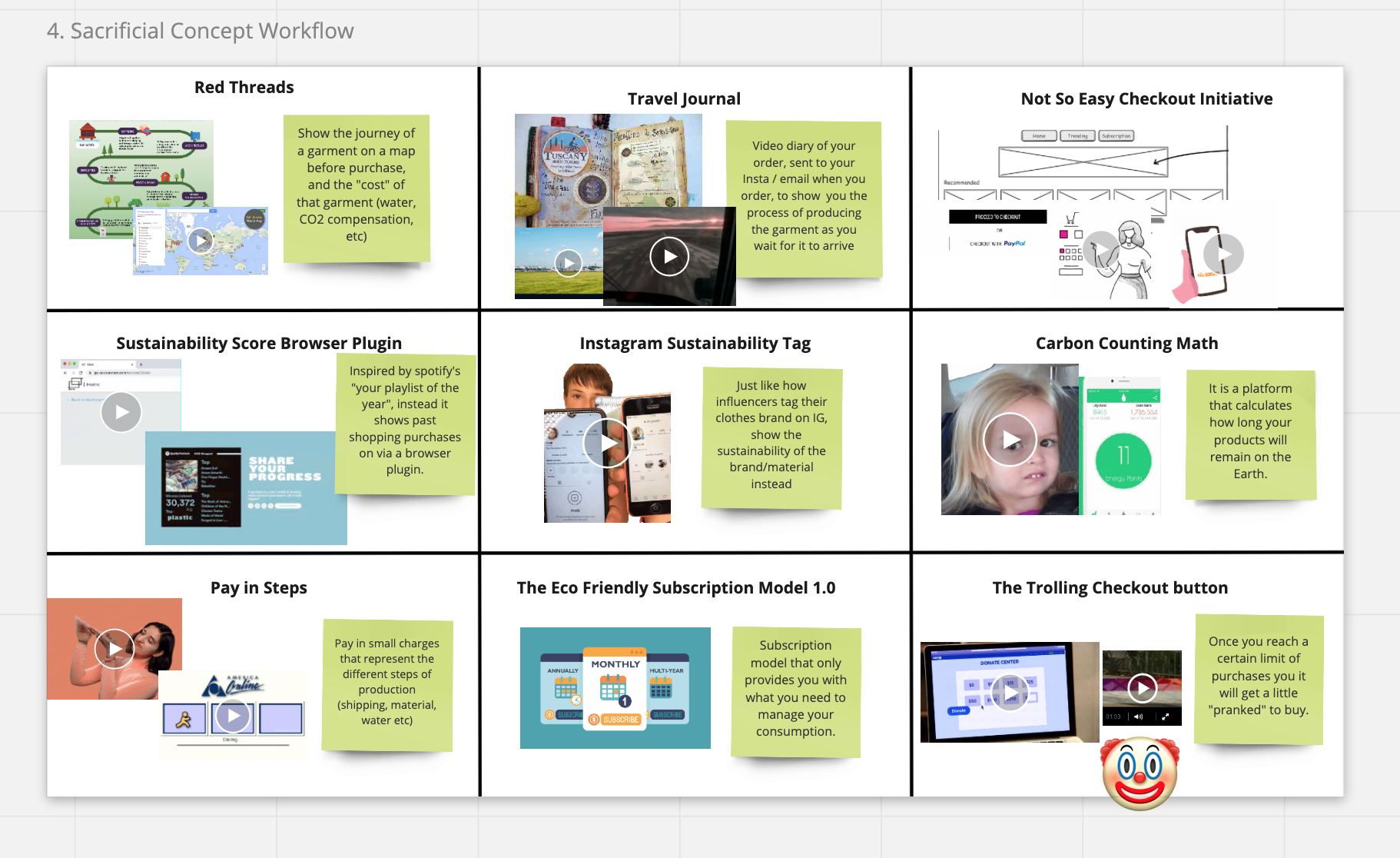

Our pressure cooker started off by doing generative research around topics mentioned in the client brief: sustainability, fashion, and online shopping. We did some trend analysis, competitor analysis, and analysed PVH's values and actions. We were also introduced to a panel of experts in sustainable fashion, who were a huge aid in understanding the possibilities of selling sustainably and how comparatively little PVH was doing with its initiatives, despite its scale. This fed into our first round of ideation and prototyping.

Our second week thus consisted of generative and descriptive research into customer shopping experiences and their attitude with sustainability. We did qualitative user- and expert interviews, in which we also showed and discussed the sacrificial concepts from the pressure cooker week.

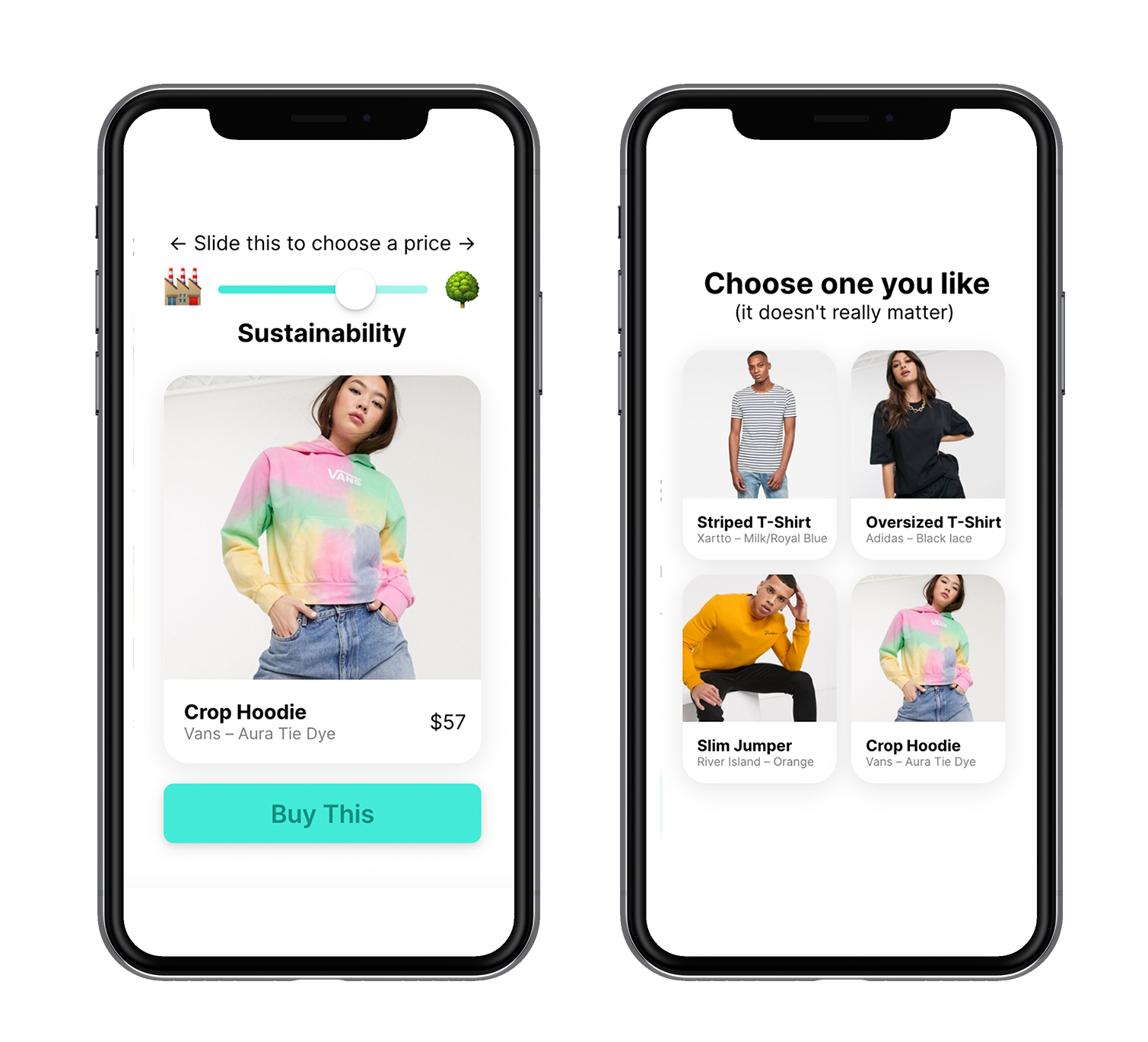

We wanted to assist our qualitative user interviews with a quantitative research method. To that end, we created a data-gathering prototype (a probotype, if you will): the "Shopping Experience Simulator". It prompted the user to pick a garment, and choose a price to pay by sliding a "sustainability" slider: worse sustainability resulted in a lower price, and vice-versa. Afterwards it asked for the customer's motivation and demographic data. This data-gathering probe was shared in our social circles and would spread to 60+ people.

Check out the generated data →Sacrificial Concepts

Source: (Howle, 2019)

What is it

Sacrificial concepts are ideas made to be destroyed. They are merely thought-provoking pitches of solutions, which the interviewee can respond to.

Reflection

The concepts provided a concrete idea to discuss instead of talking in vague hypotheticals. Users could respond more concretely to these concepts and tell us what they did or did not like about them, which gave insights into their hidden motivations.

Interviewees might feel bad about critiquing your concept(s) - this is a version of social desirability bias (Krumpal, 2011). We pretended they were examples taken from the internet to prevent the interviewee from holding back thoughts.

Probotype

Source: (Savoia, 2019; Callaghan, 2020)

What is it

The word is new, the concept is not: a prototype meant to generate data. It's similar to pretotyping, where you "fake" a product and gauge demand and viability . The difference for us lay in the desired outcome: pretotyping is evaluative research, whereas our probe was generative: we didn't have a solution to test, but wanted to understand attitudes.

Reflection

The probotype was an exciting way to gather insights from a large group of people – because of its interactive nature, completion rates were high and it was shared around a lot.

I noticed investing too much time in polishing the prototype - it should be a quick test, not a designed solution in its own right. Try to think about how to exert the least effort possible to still get the insights you want – and be clever in hacking together services and platforms to get there.

Use the probotype yourself →